2026 will define limits of Aliyev’s demands on Armenia

December 31 2025, 19:00

The diplomatic process between Yerevan and Baku, which over the past year has been presented as “the final act before signing a historic peace agreement,” in reality increasingly resembles a “moving goalposts” strategy. As soon as the sides supposedly approach consensus on one set of issues, the Azerbaijani side puts forward new, tougher conditions that affect not only Armenia’s legal framework but also its sovereign control over its own territory. Recent statements by Azerbaijan’s Foreign Minister Jeyhun Bayramov and the resonant theses of former minister Tofiq Zulfuqarov suggest that Baku has finally shifted the issue of signing peace into the realm of ultimatums, where the key element becomes the implementation of the TRIPP transport project.

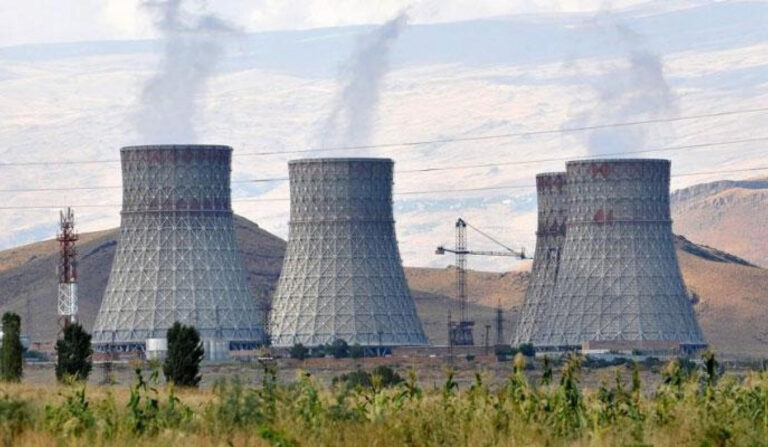

At his latest press conference, Jeyhun Bayramov outlined a new configuration of preconditions: it is no longer enough for Baku that Armenia amend its Constitution, in which the Azerbaijani side sees “hidden territorial claims.” To this list has now been officially added the demand for “full implementation of obligations under the TRIPP project.” Behind this abbreviation, known as the Trump Route, lies the condition of ensuring the movement of Azerbaijani transport vehicles through Armenian territory without customs or border checks. In essence, this is an attempt to make the acquisition of an extraterritorial corridor a prerequisite for signing a peace treaty, but under a new international label oriented toward US interests. Bayramov explicitly emphasized that the project is extremely important for Washington, trying to legitimize Baku’s demands as part of the global US logistics agenda. However, for Armenia this condition looks like a direct challenge to state sovereignty, since relinquishing control functions on its own territory would effectively turn the Syunik region into a zone of limited state presence.

The situation is further aggravated by statements from former Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Tofiq Zulfuqarov, who shifts the discussion from transit to ownership. Disputing the rights of the Russian side, represented by South Caucasus Railway, and Armenia to the railway in Meghri, Zulfuqarov invokes the succession of the Azerbaijani SSR and the Alma-Ata Declaration. His thesis that this line is the property of Azerbaijan creates a dangerous precedent. If official Baku adopts this rhetoric, the issue will no longer be about transit rights, but about claims to the infrastructure within Armenia’s borders. This drastically changes the rules of the game: instead of seeking compromise, a demand for restitution of Soviet property is put forward, which ultimately drives the negotiations into a legal dead end.

In this context, the question arises: is Baku’s current activity a preparation for peace, or merely a tactical pause? Many experts view the events of 2023, which culminated in the ethnic cleansing of Artsakh, not as the end of the conflict but as the conclusion of one of its stages. Azerbaijan’s current rhetoric suggests a strategy of wearing down Yerevan. By presenting deliberately unrealistic demands — ranging from constitutional changes to the transfer of control over roads — Azerbaijan creates a situation in which “the peace treaty becomes impossible due to Armenia’s fault.” This could serve as the perfect pretext for a new “military push.” If, however, the demands are met, Armenia ceases to be even formally a sovereign state.

The regrouping of forces and resources, evidenced by Azerbaijan’s large-scale military buildup, overlaps with diplomatic pressure. If Armenia does not agree to the extraterritoriality of TRIPP, Azerbaijan may attempt to resolve the issue by force, justifying it as the “necessity of unblocking communications.” In such a scenario, the TRIPP project turns from an economic corridor into a military route.

Analysis shows that Baku is not simply demanding peace on its own terms: it is demanding capitulation in the legal and logistical spheres, while reserving the right to a military solution in case of refusal. Thus, the peace offered by Azerbaijan today appears not as an equal agreement, but as an ultimatum deal, the cost of which for Armenia could be greater than the loss of control over its own borders.

Think about it…